7 Deep Sea Dwellers Who Hardly Look Like Animals At All

It's a different world under the sea. Animals come in many shapes and sizes on land, but in the ocean the possibilities are endless, in fact sometimes creatures don't even appear real. Unlike most land animals, the animals on this list don't have recognizable limbs, or even fins. Some are rooted to the ocean floor like plants. But none of them produce their own food, so they are officially animals - no matter how unbelievably alien they look!

1. Sponge

(Photo: Flickr, NOAA/Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute)

Sea sponges really look more like cleaning supplies than animals, but it's very likely sponges were the first animals ever, and that all animals evolved from this deceptively simple ancestor. Sponges don't have organs, but instead have an internal network of channels lined with cells that pump water through and filter out food particles. Simplicity does have its advantages. If all of a sponge's cells are broken apart, the cells can re-attach to each other and form new sponges, something no other animal can achieve.

2. Sea Cucumber

(Photo: Flickr, Dwayne Meadows, NOAA)

Even the name of the sea cucumber makes you think it's not an animal. Sea cucumbers live on the seafloor and sport tentacles around their mouths with which they catch algae and plankton to eat. If sufficiently threatened, sea cucumbers deploy one of nature's oddest defense mechanisms: they shoot their attacker with their own internal organs, and skedaddle while the animal is entangled. It takes about six weeks, but the sea cucumber's organs will grow back, ready to serve as ammunition when needed.

3. Coral

(Photo: Flickr, Brent Deuel, NOAA)

When you think of coral, you probably first think of coral reefs. Reefs form over centuries as individual coral polyps live, secrete hard limestone outer skeletons, and then die on top of each other. Live polyps have soft bodies and tiny tentacles around their mouths, which they use to collect whatever food drifts by, namely very small fish and zooplankton (see number 7). By leaving behind their secreted skeletons to build reefs, coral polyps literally provide foundations for ecosystems of astounding biodiversity.

4. Sand Dollars

(Video: YouTube/Sea Something)

Before drying into the rough white disks ubiquitous in beach souvenir shops, live sand dollars are dark purple animals covered with small spines. Sand dollars use their spines to sweep plankton and crab larvae into their mouths, to burrow into the sandy seafloor, and as gills. Along with some fish species, sea stars prey on sand dollars.

5. Giant Tube Worms

(Photo: Flickr, NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Galapagos Rift Expedition 2011, NOAA)

Giant tube worms make their homes at hydrothermal vents, cracks in the deep ocean floor that release volcanically heated and enriched water. They rely on bacteria living inside them to process the chemicals in this water into nutrients they can use. Giant tube worms only have stomachs temporarily as larvae, long enough to ingest bacteria that will feed them the rest of their lives. After attaching to the ocean floor and growing their tubular exoskeletons, made of the same material as crab shells, they never need to eat again.

6. Pompeii Worm

(Photo: Ravaux J, Hamel G, Zbinden M, Tasiemski AA, Boutet I, PLoS ONE)

It may look more like an animal than the others on this list, but it's more surprising the Pompeii worm is actually alive, given the high temperatures it endures living attached to hydrothermal vents. It survives blasts of water as hot as 176 degrees Fahrenheit, despite the scientific consensus that animals can't tolerate temperatures above 122 degrees. How it manages remains a mystery, but scientists think the hair-like bacteria on the Pompeii worm could act as insulation against the heat.

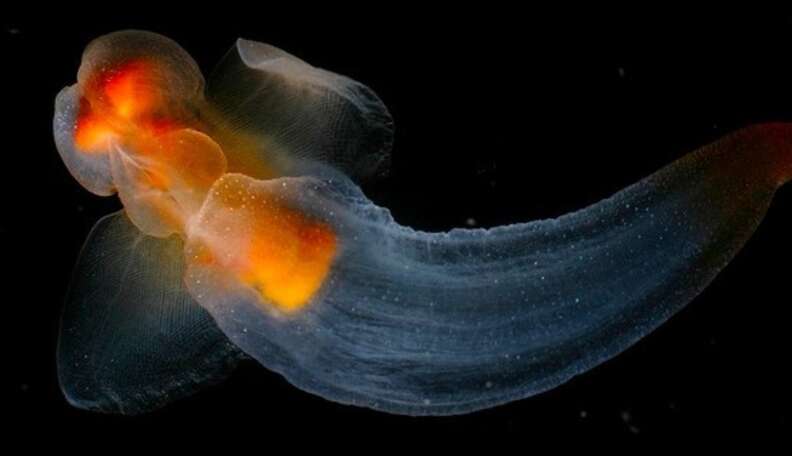

7. Sea Butterflies

(Photo: Flickr, Kevin Raskoff, NOAA)

Smaller than a grain of sand, the sea butterfly is one of many miniscule animals classified as zooplankton. Several species of fish and seabirds feed on sea butterflies in the polar oceans where they constitute half of the total zooplankton population, making them the base of the food chain. These mollusks produce very thin shells of calcium carbonate, which is increasingly scarce in an ocean growing more acidic from absorbing carbon dioxide. One of the ocean's tiniest animals is also one of its most essential - and at risk.

Like all life in the sea, these animals are vulnerable to the effects of climate change, particularly rising ocean temperatures and ocean acidification. They may not be cuddly, they are still animals all the same.